2022 Update: After a long gestation period (prolonged by obvious world events), the full and final version of this research was recently published in the journal Music Theory Online. If you’ve found your way here via Google, or maybe that Adam Neely video, you might be interested in seeing the more developed version of these ideas rather than reading this draft-y blog. And you might be particularly interested in the better-illustrated examples in the full article (more examples! more transcriptions! much better transcriptions! animated videos!) You can find that full version here, in MTO’s September 2022 issue.

I’m posting the “Director’s Cut” version of my SMT 2019 talk here. After delivering it at the conference two weeks ago, I gave a slightly expanded version (mostly restoring things I had to cut for time, adding the “Final Countdown” case study, and playing more than 20-30 seconds of each example) here on campus at our Friday lunchtime talks series. I’ll probably revisit this post in the coming days (and remove this part of the disclaimer) and make things a little more blog-like: links not endnotes, etc. Because really, end notes are terrible.

The Techne of YouTube Performance: Musical Structure, Extended Techniques, and Custom Instruments in Solo Pop Covers

While we often hear that Spotify, Pandora, Apple Music, and other services have taken over the music industry, the 2018 Music Consumer Information Report tells us that these are not even close to cornering the market on streaming music. Because for several years now, the most popular way to stream music, worldwide, has been YouTube, which accounts for 47% of all streaming music.[1] In other words, YouTube is the biggest place that people go to listen to music today, and it’s not even close.

Today, I’d like to talk about the portion of YouTube’s vast music library that is made up of cover songs by amateur and independent musicians. YouTube covers vary in genre and style, from straight-ahead, full-band performances; to solo acoustic renditions; to other, less common solo instrumentals, like Coldplay done on a marimba.

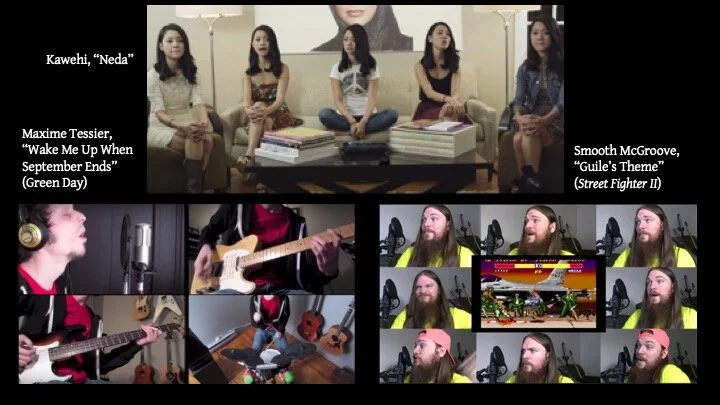

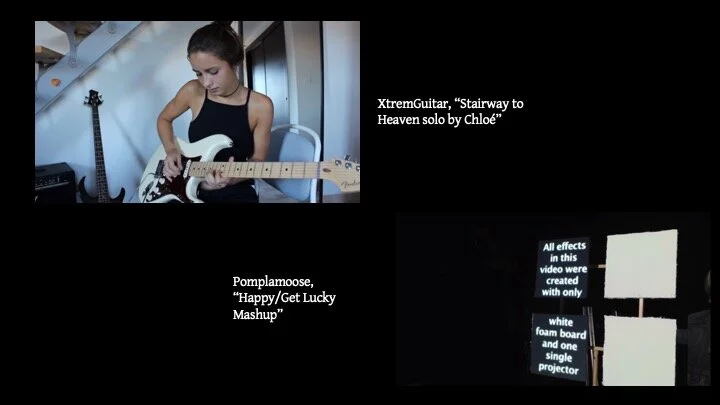

Some of them are serious, some of them are humorous. There are faithful recreations, which pay tribute to the original recordings by trying to stay as close as possible to the source material; and there are adaptations and interpretations. There are even “mashups” of two or more songs. Some artists embrace the artifice of YouTube, green-screening or image masking themselves into a power trio, a vocal quintet, or even more.

Others are naturalistic, emphasizing their liveness or lack of effects, as in the unadorned basement seen in the background below. Or, perhaps they their intricate, well-rehearsed audiovisual constructions, executed in single takes ala Hitchcock’s Rope. Regardless of the particular style, it is clear that since it launched on Valentine’s Day 2005, YouTube has become a platform for creative musical expression of all kinds.

Today, I’m interested specifically in the phenomenon of the solo cover. This ascendant genre draws together traditions old and new, from the “one man band” of the nineteenth century, to the experimental live looping of 1980s performance art, to the techniques, equipment, and software now readily available to many amateur musicians. These videos often begin with a single note, a chord, the tap of a button, or the triggering of a loop. Through progressively layered textures, samples, or extended performance techniques, musicians on YouTube love to construct their cover songs piece by piece before the eager eyes and ears of their viewers. These intricate arrangements and performances combine virtuosity and novelty in a package ready-made for viral online popularity.

I’m going to explore a series of recent popular YouTube videos in order to study the ways in which amateur musicians craft such arrangements through a combination of creativity and music-analytical understanding. The case studies I’m presenting today all have several things in common. First of all, they feature performances that are virtuosic in several ways. These brands of virtuosity range from the traditional notion of dazzling instrumental technique; to a precise craft, or a command of a large array of acoustic instruments and electronic devices. They also feature what I have come to think about as a form of “music-analytical virtuosity,” or perhaps a virtuosity of arrangement. What I mean by this is that the musicians I have been studying all display a knowledge of song structure and form, and in some cases, a keen understanding of harmony, which they call upon in order to craft their arrangements. Finally, they all place the musician’s labor front and center. While, as we will see, many of these videos are thoroughly rehearsed and highly polished, they often allow the audience a peek behind the curtain, showing us just how much preparation and work goes into crafting a three-minute pop song.

A number of recent studies in musicology have sought to take into account the affordances and restrictions of writing and performing music on various musical instruments, from piano keyboards, to various stringed instruments, and even laptops, turntables, and electronic sampling. Anna Gawboy (2008), for example, has demonstrated how the two-handed arrangement of buttons on the Concertina affects how its players voice their chords, while Jonathan de Souza (2018) has demonstrated how what he calls “fretboard space” intersects with the shape of the human hand in the neo-Baroque guitar solos of Eddie van Halen. This presentation builds on these studies by examining how YouTubers use theoretical and instrumental expertise to convey complex textures through a minimal collection of musical materials. In each of these cases, the instruments themselves are arranged, modified, or even created in order to make these performances possible. Through their sparse, economic construction, these intricate arrangements are each the end product of a careful analysis of each song, and they have much to teach us about the harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic structures of popular music. There are two very quick surveys to make in order to establish some theoretical background for these videos: I would first like to spend a moment thinking about instruments, technology, and music theory, and then I will conduct a brief survey of theories of the cover song.

Theories of the Cover Song

Theoretical and historical accounts of rock covers have either drawn comparisons between cover songs and a long history of musical borrowing—from parody masses and contrafacta through mashups and samples—or have attempted to describe what makes cover songs unique to the genre of rock. Taking the former tactic, Serge Lacasse (2000, 45–47) describes covers as just one among many, many forms of musical intertextuality; covers, for Lacasse, are characterized by interpretive readings they offer of existing music, or their propensity to transplant a song into the stylistic milieu of the covering artist. Taking the latter point of view, Gabriel Solis (2010) argues that covers are intrinsic to rock, that they structure its history in a way that is distinctly different from, for instance, orchestras performing the same piece of Classical music, or multiple jazz musicians recording the same standard. Theodore Gracyk (1996) doubles down on this ontology, defining rock as a medium concerned entirely with recordings, and citing the prevalence of covers as a primary source of evidence. As Michael Rings (2013, 56) points out, covers carry an expectation of creative transformation: a cover that mirrors exactly the original recording would be considered a failure. Finally, in a very recent paper, Ed Klorman (2018) points out how a performer’s mannerisms, or even the performer’s identity, can affect how we hear the message of a cover song, as evidenced by Cyndi Lauper’s famous version of what was originally a punk song with a very different message, “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun.”

Techné

In describing this activity the title of my paper, I am borrowing the word techné from ancient Greek philosophy. In a basic definition, techné (which is often translated as “craft,” or sometimes as “skill” or “art”) can be opposed to episteme (or “knowledge.”) However, in most accounts of the two ideas, from thinkers like Plato and Aristotle, through modern interpreters like Heidegger, techné and episteme are not black and white opposites: they inform each other. Techné is practical knowledge or the ability to produce something, that includes theoretical knowledge. Tellingly, in Plato’s dialogue Sophist (1997, 348 / §252–253), music theory is described as techne: the expertise that a musician has in knowing which notes go well together and which do not. So what I hope to sketch today, then, is a certain conception of musical techné that is embodied by YouTube covers: a form of music-theoretical knowledge that is informed both by practical, instrumental considerations, and virtuosic performance. Or, perhaps from another angle, it is a form of performance practice that depends on musical knowledge. In other words, the insights of analysis and the conditions of performance cannot be separated from one another—they come together in these transformatively minimalist arrangements.

Pupsi performs Toto’s “Africa”

Our first example features a solo cover created by overdubbing parts, and performed on a very memorable set of homemade instruments. Instrument maker and musician Toni Patanen opens his cover of Toto’s “Africa” with an extended montage of himself making a series of instruments out of vegetables—yes, vegetables—by hollowing them out, boring holes, and tuning them. Patanen, who goes by “Pupsi” on YouTube, makes his living partly by selling actual ocarinas online, made much more traditionally out of clay, rather than butternut squash.

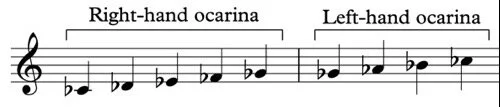

Over the first 90 seconds of the video, Patanen crafts two small ocarinas out of sweet potatoes, and a larger one out of a butternut squash. He carves out the centers, bores holes in the sides, and tunes them with the aid of a Casio keyboard. The gamuts of the smaller instruments are dictated by the distinct registral shift that characterizes each line of “Africa’s” verse, as shown here. The first half of each line explores the upper fourth of the major scale, while the second half lies only in the lower fifth. Presumably, the tonal range of a sweet potato is relatively limited, making this division both serendipitous and necessary. (That last sentence isn’t going to help convince my in-laws that music theory is a real career.)

Sweet Potato Ocarina gamut

Nope, still haven’t re-transcribed this in B major…

But in all seriousness, I’ve chosen this example not only for its musical qualities, but for how well it exemplifies the entire genre of the solo YouTube cover. The video begins with Pupsi setting the scene: the veggies are deposited roughly on the table, and then transformed, through a series of fluid movements and a rapidly cut montage, into instruments. Their insides are hewn out with broad knives, and we watch Pupsi tune each ocarina against his keyboard. Then, finally, one minute and forty seconds into a four-minute video, the song finally begins; clearly we are here for the journey, not just the destination. From there, Toto’s “Africa” is played as straight as one can hope to perform an 80s hit on hollowed-out root vegetables. A three-way split screen separates the double sweet potato ocarina melody, from the butternut squash’s bass line, from the additional middle voice that fills in the texture when necessary. Along with its novel format, Patenen’s cover is a re-presentation of a song that has become an internet cliché, or a “meme,” as Paula Harper defines it in her 2019 dissertation, “Unmute This”: it is a cultural object that is meant to call to mind other variations on the same theme, and indeed draws much of its humorous meaning from that relational network.

Luca Stricagnoli Performs Michael Jackson’s “Thriller”

Guitarist Luca Stricagnoli maintains a YouTube channel filled with covers of popular songs, many of which feature him playing two guitars at once. He accomplishes this through a combination of careful musical arrangement, instrument modification, and virtuosic technique. Stricagnoli’s performance of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” for example, sees him using virtuosic left-hand techniques to articulate the bass line on one guitar, while performing the melody on a second guitar that has been retuned in diatonic steps.

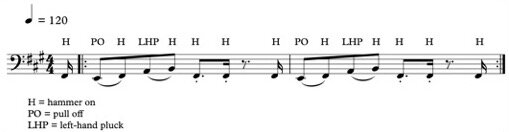

There are several things to note about Stricagnoli’s performance. The first is his virtuosic, one-handed performance of “Thriller’s” memorable bassline, as shown here. Using a combination of hammer-ons, pull-offs, and left-handed plucking, he is able to perform the bassline with only one hand, on the guitar that he holds traditionally. Another aspect is the realization that the melody from Thriller’s verse contains six—and only six—notes. The second guitar, placed flat on the table and played only with open strings, is tuned in diatonic steps rather than fourths and a third. So while one hand combines a series of techniques that are in the guitarist’s standard repertoire, the other uses a performance technique based more on the harp than on the guitar, to render the melody in ringing, open strings. This second guitar also has a piece of cardboard taped to it, on which Stricagnoli taps the backbeat with his thumb in between melodic notes. For each chorus and the bridge, finally, Stricagnoli plays the first guitar, two-handed in the standard way. His capacious and polyphonic left hand marks him as Classically trained, as he performs both melody and harmony clearly.

Bass line from Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” as performed by Luca Stricagnoli

Re-tuned open strings in Luca Stricagnoli’s cover of “Thriller”

In Stricagnoli’s cover of Michael Jackson, we hear two forms of transformation: first, his virtuosic performance, which uses extended techniques to bring out the song’s recognizable bass line, and the unusual second guitar, laid out on the table. Second, that performance technique is itself made possible by a careful analysis of the song, whether through trial and error, or an intentional exploration of the verse’s simple melodic and harmonic structure—one of the two helped Stricagnoli recognize how he could re-tune a guitar to play the melody on the open strings, thereby opening the door to the left-handed tabletop performance.

Kawehi Performs Nirvana’s “Heart-Shaped Box”

Kawehi is an independent singer-songwriter based in Lawrence, Kansas. In addition to touring and recording, Kawehi has been active on YouTube since 2013. Her videos are often both technically and musically creative, chronicling her solo performances of both cover songs and original songs. Some of Kawehi’s performances take advantage of multitrack recording—she was that vocal quintet I showed in an early slide—while others employ “live-looping” technology. Live-looping is a practice in which short segments of music are recorded and then played back, so that a musician may accompany themselves. Long an analog practice associated with performance artists like Laurie Anderson—and dependent on literal tape loops, before the advent of digital looping devices in the 1990s—live-looping is now popular among indie musicians on YouTube, driven either by floor pedals, or computerized through software such as Ableton Live.

Kawehi’s gear is an integral part of her online persona. In her self-presentation to her fans, she often posts behind-the-scenes videos of herself preparing to go on tour, or demonstrating her rig. This image comes from her Instagram account, and it depicts the arrangement that we’ll see and hear in just a moment.

Kawehi’s 2014 cover of Nirvana’s “Heart-Shaped Box” opens with the sense that we are “before the beginning.” Kawehi looks askance at a second camera, which bobs as if its tripod is still being adjusted. She speaks into the microphone: “Yup, yup, is this thing on?” As the harmonizer splits her voice into cacophony, she demonstrates the tool that will underlie nearly her entire performance, an effects processor that harmonizes with her voice in real time. “She sings triumphantly in response to her own question; given a pitch to grab onto, the black box's voices coalesce into a chord, supporting her cry with a deep bass tone and a piquant minor third.

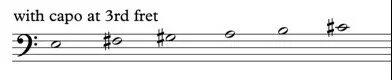

As the video gets underway, we get nearly two minutes of Kawehi recording and looping musical fragments: keyboard drones, synthesized guitar riffs, backing vocals, and beatboxing. As shown here, she records two simple vocal loops. One is a single pitch, A, which is then harmonized by Ableton with a minor third above, and an octave below. The other, which begins the song, goes A to F#, again harmonized with C and A above, and then her original voice an octave low. She triggers these sampled dyads throughout the song’s primary three-chord progression, which she slowly begins to flesh out with synthesizer parts. As we’re about to see and hear, Kawehi records numerous fragments of the song, and she does so in a very careful order: the “post-chorus loop,” which comes last in the song structure, is recorded first, so that she can come back around to it at the end. Even the introduction, then, is carefully structured: many of its most distinctive portions—the guitar riff which will double the vocals, or the shout that begins the video—are recorded early, and then seemingly forgotten about until later. From the end of the introductory chorus, Kawehi steps seamlessly into the first verse.

Kawehi, “Heart-Shaped Box,” Introduction [Rough transcription]

That A-C dyad is made useful as a device to knit the song together by the song’s third-related chord progression: A minor, F major, D7. A and C participate in each of these chords, re-contextualized by the moving bass line. The dyad is only silenced when the harmony changes at the end of each chorus. Even more interestingly, the “post-chorus loop” features two dyads created by the harmonizer: A-C, and F#-A. In both cases, Kawehi’s minimal arrangement very cleverly takes advantage of the role played by minor thirds in each of the song’s three chords: she can sing so few notes because the A-C dyad forms the bottom of A minor, the top of F major, and the top of D7. In the truncated version, with two dyads, A to C forms the top of F major, while F# up to A forms the middle of D7.

Analysis

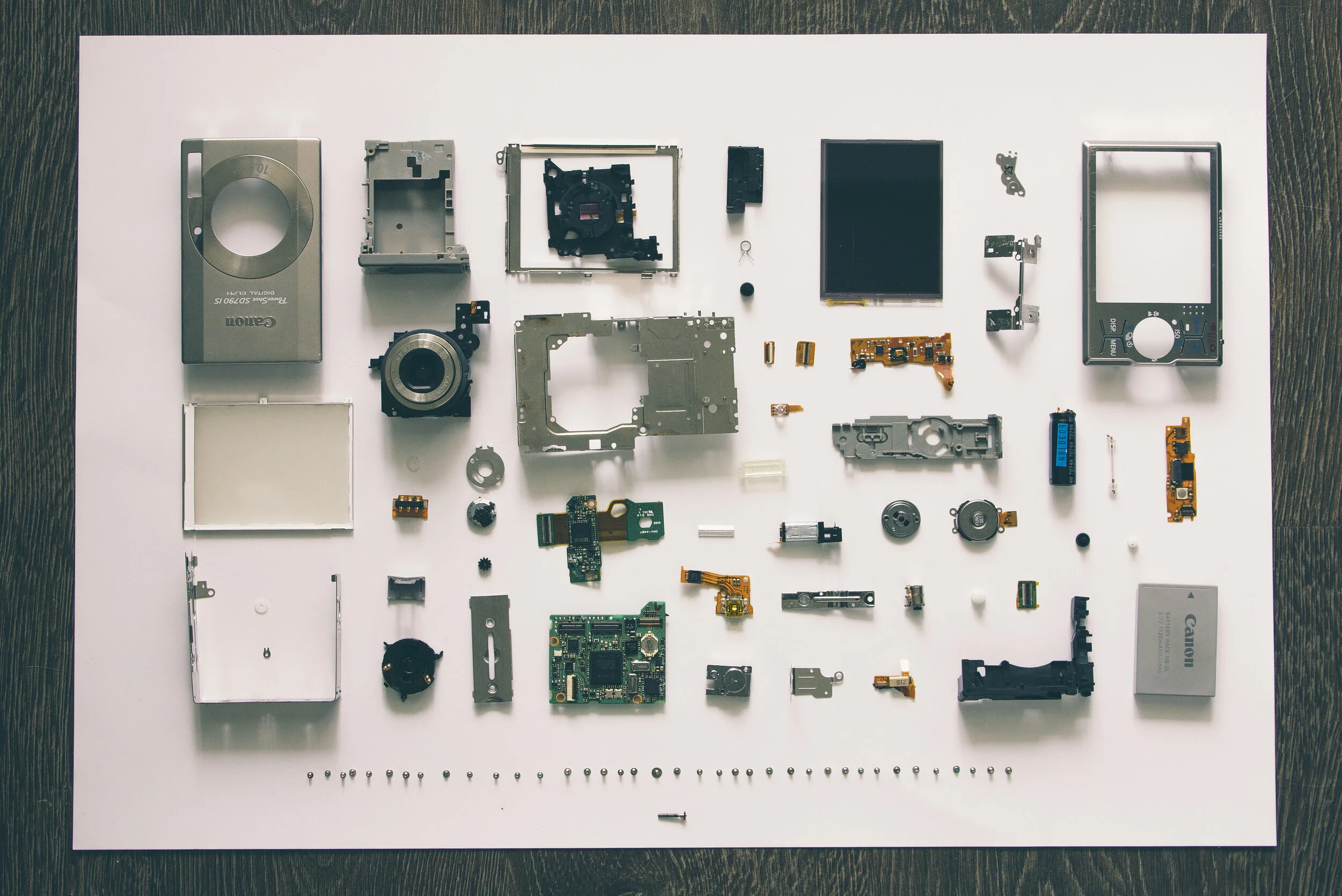

Videos like Kawehi’s anatomize the music for the audience, laying out the constituent parts like so many pieces of a complex device on a table. It’s the “Chekov’s gun” effect, the musical equivalent of James Bond being given his gadgets in the first act of a 007 movie: we know that by the end of the film, someone is going to be launched from the ejector seat. As Theodore Gracyk has written, the communicative potential of a cover song comes from the expectation that the audience is familiar with the original. Transformation often happens by changing instrumentation—as in stripped-down acoustic covers which replace a full-band arrangement with only a singer and a guitar—or by crossing genres, as in famous and much-discussed covers like the Sex Pistols’ 1979 fast and profane version of “My Way,” or Tina Turner’s upbeat 1971 version of “Proud Mary,” a transformation of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s hit from two years earlier.

The transformation in the cover songs presented in this talk relies in large part on familiarity with the original as well. The sense of wonder and amusement that leads many users to click “Share” comes from viewing the deconstruction of a familiar song. “Heart-Shaped Box,” for instance, is anatomized for the listener. It coalesces out of a cloud of abstract vocalizations, as Kawehi adds first a backbeat, and then a bass line that gives shape to that pivotal minor third. It is not until she plays the memorable guitar riff from the chorus that what we are hearing becomes clear, and anticipation begins to build for the first line of the verse.

Aspects of each individual performance are important as well. For Pupsi, there is a potent combination of the novelty of carving out instruments from root vegetables, and the impressive technical prowess necessary to do so successfully. In Kawehi’s “Heart-Shaped Box” cover, she deftly balances numerous samples, combining live performance with a carefully choreographed set of samples, recorded in isolation and triggered in various combinations: a hybrid performance of rock vocals with the multitasking of an orchestral conductor. Finally, in Luca Stricagnoli’s “Thriller,” the audience is engaged by both the spectacle of watching the two guitars—a nominally two-handed instrument—played one-handed, in such an unusual and technically challenging way.

I believe it is this pair of aesthetic moves -- radical transformation and delayed gratification -- that grant much of the pleasure taken in watching videos such as these. I’ve got one more brief case study to explore this more fully, and to launch us into the final analysis—a case study that YouTube recently brought to my attention, while I was working on this talk. The nice thing is that if you study YouTube enough, the front page algorithm catches on and just serves up new examples for you to analyze. In this case, my feed recently introduced me to a new channel, entitled iSongs. iSongs is run by a single musician who refuses to show their face; they perform—or perhaps more accurately, construct—cover songs using the iPhone’s version of the popular music creation app “GarageBand.” In this cover of Europe’s “The Final Countdown,” as we have seen before, the performer works through all the different parts of the song—constructing the drum groove, the bassline, the keyboard accompaniment. Most importantly of all, they save the famous synthesizer riff, the song’s most recognizable feature, until very late. Tension builds for nearly five minutes out of a six minuet song, until the recognizable synthesizer finally breaks through with the song’s famous introduction.

This final example raises the specter of musical labor. Amidst all that delaying of the riff, there is a smooth and well-choreographed dance of fingers across the virtual keypad. Just to enumerate what we see in only a couple of seconds: We see him set the tempo, we see him select each and every instrument, quantize them precisely (quantization is a tool that essentially smooths out mistakes, by making sure that each musical attack falls on a recognizable beat). We see him switch tracks, counting each one off carefully. We see him build drum beats up from glowing boxes

Aside from iSongs, Kawehi is perhaps the best exemplar of musical labor in action: her videos and album covers are fixated on her relationship to technology; catchy little vignettes of cybernetic anxiety. In the original song “Anthem,” she uses special effects to acknowledge how live-looping instrumentalizes the voice, disrupting the semiotic plentitude often attributed to human singing. Here, she repeatedly pulls her own head off, each time labelled with the quasi-mechanical musical function it is playing.

Album cover for Kawehi’s Evolution (2016)

The album cover art leans into this machine-mediated musicking as well, casting Kawehi as a cyborg, in what has become a familiar aesthetic in recent science fiction: the imagery echoes the stylings (and the robotic limbs) of Ex Machina (2015), a mediation on the nature of artificial life. There are shades of Donna Haraway’s famous “Manifesto for Cyborgs” (1985) here, with Kawehi’s self-mechanization subverting the notion that our machines are “made of sunshine…all light and clean because they are nothing but signals” (1985, 70). Kawehi’s YouTube stylings emphasize the human agency that drives today’s musical technologies, while also offering a warning of how quickly humanity can disappear into that technology. Musicologist Susan McClary’s description of the 1980s live-looping of performance artist Laurie Anderson might well apply to Kawehi’s YouTube performances:

“[H]er compositions rely upon precisely those tools of electronic mediation that most performance artists seek to displace. … most modes of mechanical and electronic reproduction strive to render themselves invisible and inaudible, to invite the spectator to believe that what is seen or heard is real. By contrast, in Laurie Anderson’s performances, one actually gets to watch her produce the sounds we hear. But her presence is always already multiply mediated: we hear her voice only as it is filtered through Vocoders, as it passes through reiterative loops, as it is layered upon itself by means of sequencers. … The closer we get to the source, the more distant becomes the imagined ideal of unmediated presence and authenticity. (McClary 1991, 131)”

Along with their musical qualities and their meditations on technology, solo YouTube covers reflect their online medium, in the way they mirror and participate in the evolving aesthetics of the social web. Several years ago, the critic and writer Paul Ford wrote an essay on Medium that describes “the American room”: a generic space, often beige, usually filmed from the upward angle of an open laptop. The American Room, a product of sparsely decorated suburban apartments, was ubiquitous in YouTube’s early days.

That look has given way, however, to something much more polished: Kawehi’s studio might well be a page from a Restoration Hardware catalog, while Luca Stricagnoli has been professionally lit and dynamically filmed, the camera swooping around him as he performs. Both are a far cry from a MacBook camera in a two bed, two bath condo, the kinds of spaces that dominated YouTube’s first decade. And we can see in these luxurious spaces a certain resonance with another distinctive aesthetic of Instagram and Tumblr: gear fetishism. Popular among photgraphy enthusiasts, images such as they one below feature tools of the trade, carefully laid out on rich-hued tables. Here, the impressive array of technology is almost more important than the landscapes or portraits that might be captured with them. Everything, again, is laid out and disassembled for the viewer; anatomized on the table like so many chords in a cover song.

Cover songs—and the various forms of multimedia that currently surround them in popular culture—are a vital area for investigation, as a way of understanding and untangling many of the aesthetic issues in music, from originality to creativity, authorship to transformation and transcription. As the frisson of recognition collides dramatically with the unfamiliar affect of humor, a dazzling technique, or complex web of loops, a cover song forever changes our understanding of the original tune. After this presentation, I defy you to listen to any of these songs—or to look at a butternut squash—in the same way again.

Selected Bibliography

Boone, Christine. 2013. “Mashing: Toward a Typology of Recycled Music.” Music Theory Online 19(3).

Bungert, James. 2015. “Bach and the Patterns of Transformation.” Music Theory Spectrum 37/1: 98–119.

Butler, Mark J. 2014. Playing with Something That Runs: Technology, Improvisation, and Composition in DJ and Laptop Performance. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Cayari, Christopher. 2017. “Music Making on YouTube.” In The Oxford Handbook of Music Making and Leisure. Edited by Roger Mantie and Gareth Dylan Smith. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

De Souza, Jonathan. 2017. Music at Hand: Instruments, Bodies, and Cognition. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

De Souza, Jonathan. 2018. “Fretboard Transformations.” Journal of Music Theory 62/1: 1–39.

Dolan, Emily I. 2010. “’This little ukulele tells the truth…’: Indie Pop and Kitsch Authenticity.” Popular Music 29/3: 457–469.

Dolan, Emily I. 2012. “Toward a Musicology of Interfaces.” Keyboard Perspectives 5: 1–13.

Gawboy, Anna. 2009. “The Wheatstone Concertina and Symmetrical Arrangements of Tonal Space.” Journal of Music Theory 53/2: 163–190.

Gracyk, Theodore. 2012/13. “Covers and Communicative Intentions.” Journal of Music and Meaning 11: 23–46.

Harper, Paula. 2019. “Unmute This: Circulation, Sociality, and Sound in Viral Media.” Ph.D. diss., Columbia University.

Klorman, Edward. 2018. “Performers as Creative Agents; or, Musicians Just Want to Have Fun.” Music Theory Online 24(3).

Lacasse, Serge. 2000. “Intertextuality and Hypertextuality in Recorded Popular Music.” In The Musical Work: Reality or Invention? ed. Michael Talbot. Liverpool University Press.

Malawey, Victoria. 2010. “An Analytical Model for Examining Cover Songs and Their Sources.” In Pop Culture Pedagogy in the Classroom, ed. Nicole Biamonte. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Miller, Kiri. 2012. Playing Along: Digital Games, YouTube, and Virtual Performance. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Mosser, Kurt. 2008. “‘Cover Songs’: Ambiguity, Multivalence, Polysemy.” Popular Musicology Online 2.

Parry, Richard. 2014. “Episteme and Techné.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/episteme-techne/.

Plato. 1997. Plato: Complete Works. Ed. John M. Cooper. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

Rockwell, Joti. 2009. “Banjo Transformations and Bluegrass Rhythm.” Journal of Music Theory 53/1: 137–162.

Solis, Gabriel. 2010. “I Did It My Way: Rock and the Logic of Covers.” Popular Music and Society 33(3): 297 – 318.

Schiffer, Sheldon. 2016. “The Cover Song as Historiography, Marker of Ideological Transformation.” In Play it Again: Cover Songs in Popular Music, ed. George Plasketes. London: Ashgate.

[1] https://www.ifpi.org/downloads/Music-Consumer-Insight-Report-2018.pdf

[2] Susan McClary, Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991), 137.

![Kawehi, “Heart-Shaped Box,” Introduction [Rough transcription]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53777798e4b0875c41487b50/1574451081592-3AJAJ2P891SFKUKYVXFQ/Kawehi+new+3.jpg)